Normally, one cools down after working or exercising hard. In remote viewing, the cool-down comes first.

It was Thursday, January 19, 1984. We were in the windowless, highly-secret consciousness research facility on the top floor of SRI-International’s Radio Physics Laboratory building in Palo Alto, California. And it was time for my first remote viewing session with the illustrious Ingo Swann.

The “we” I mentioned consisted of four people—Bill Ray, Ed Dames, Charlene Shufelt, and myself. We had just wrapped up three and a half days of lecture and essay writing under the guidance of our master remote viewing instructor, Ingo. And now, on the afternoon of the fourth day, we were going to try our first Stage 1 remote viewing sessions.

Anxiety Happens

It would be an understatement to say we were nervous. Here’s how I described the experience in my book Reading the Enemy’s Mind:

The moment of truth had arrived…I don’t think that any of the four of us looked with total eagerness on the prospect of our first remote viewing sessions. Even the hours of lecture and essay writing couldn’t quell those same feelings we had experienced back at Fort Meade before doing our very first outbounder remote viewing sessions — feelings of excited anticipation, fear of failure, and dread of the unknown.

Charlene Shufelt recently reminded me she was scared to death while she waited for Ingo’s voice to echo, “Next!” out of the bowels of the remote viewing grey room.

At the time, none of us had any consistent experience with preparing for a remote viewing session. This game would eventually become old hat for us, with hundreds and thousands of sessions under our belts. But for this first attempt at CRV, all I could manage was reading a little in a book, lightly dozing for a few minutes—basically, trying to relax, or “cool down,” as we came to call it—marking time until it was my turn to go through the door.

Cool Down

This introduces the topic of “cool-down.” The question of cool-down comes up regularly in various remote viewing forums. “What do you do to cool down?” I’m often asked. Or, “Is it really necessary to cool down?” Or other variations on the theme.

I first was introduced to the idea of cool-down in the very early days of my assignment to the Star Gate program at Ft. Meade, Maryland in September of 1983. But it wasn’t as a prelude to a CRV session—since my first CRV experience, as described above, was yet in the future. Instead it was in preparation for an ERV (for “extended remote viewing”) session.

To get me ready for these experiences, Fred “Skip” Atwater, our training and operations officer, directed me to lie down, don stereo headphones, and listen to what I was told were Hemi-Sync signals. Out-of-phase tones were played into my ears that were intended to create harmony between my left and right brain hemispheres. This audio input came in a variety of frequency combinations, but the two we used most were called “Focus 10″ and “Focus 12.” The result was a very relaxed “mind awake, body asleep” state which, I have to say, did work wonders for my stress levels. And it seemed to me to be a good preparation for doing remote viewing work.

My Cool-down Evolved

Over time we used the Hemi-Sync prep less and less for our ERV sessions. Once you got the hang of Hemi-Sync, it seemed you could set up that same altered state without the need for an audio signal. At least, so it appeared true–at least for me.

We did not use Hemi-Sync as “cool-down” for CRV sessions. But thanks to the Hemi-Sync experience I had by then gotten used to the idea of a pre-session cool-down, and developed my own as prep for any session I did. About 20 minutes before I was due to start remote viewing, I would go over to the operations building, where we did all our actual remote viewing work at Ft. Meade. I would stretch out on the bed in the ERV room (we may have been the only intelligence activity in the entire military to have a bed as part of our operational equipment), put on headphones and click on my portable cassette tape player.

Into my ears and brain would flood whatever mix tape I had brought in to work that day. My tapes were mostly compilations I had made at home of heavy metal and what counted for hard rock back then, such as AC/DC, Black Sabbath, Molly Hatchet, Def Leppard, Deep Purple, Quiet Riot, Twisted Sister and Rainbow, among numerous others. There was also Foreigner and Journey, plus a couple of Bon Jovi songs. But there were less driving pieces as well. I had a couple of Dolly Parton songs, some Dire Straits, one or two from Tom Petty, and a fair amount of Pat Benatar, among many others. Upon hearing about my typical playlist, people often wonder how such aggressive music could possibly contribute to a “cool-down.” And yet it did.

Cool-down as Motivator

For me, relaxation wasn’t the most important ingredient of my cool-down (though it helped that as well). A more significant role was to motivate and encourage me for what I was about to do. You see, I always went into these sessions full of doubt. (I even still do, though to a lesser degree.) And I sincerely question whether any successful remote viewer looks forward to a session without some question as to how he or she will perform. If someone tells you that they don’t have at least little uncertainty when going into a session, they are either fooling themselves about not being doubtful—or they’re fooling themselves about being a successful remote viewer.

Here’s the bottom line for me: It wasn’t about what music genre I chose for cool-down. It was about how the music made me feel. I’ve often described my cool-down as being like a pre-game pep talk for a high school football team (or wrestling squad, since that was the sport I participated in).

Anyone who has been in high-school sports knows what I’m talking about. The coach calls all the team members together, and then alternatively cajoles and exhorts them. “You can do it!” is the message. The coach is trying to raise confidence levels, enthusiasm and just plain raw determination, since he knows those are the key to success. Without them, it doesn’t matter how good you are. Unless the other team never shows up for the game, if you lack confidence and determination, you are very likely to lose.

I was using music to boost my confidence and determination in the face of doubt and uncertainty. And it seemed to work.

But, as is often the case, there may be more to the story.

The Surprising Importance of Ritual

One of my courses in graduate school at the University of Texas, Austin focused on behavioral learning. As part of the class, I learned the importance of ritual in settings where it never would have occurred to me to look.

A particularly interesting piece of instruction from the professor was ritual mattered even in drug addictions. He explained that many heroin overdose deaths don’t involve the addict using any more heroin than he or she normally does. It goes like this. Typically, the addict always retires to the same specific place to shoot up, then goes through the same usual steps in the same usual order, using the same items to complete the process.

But now suppose that for a few days the heroin supply is interrupted. Cravings are amplified by forced abstinence. So when able once again to score a supply, the addict rushes off to find any nearby secluded place, and uses whatever means are at hand to consume the narcotic. Overdose—and often death—immediately follow. How did this happen? After all, no more heroin was taken than usual.

What is different is that the ritual was missing—the ritual of an habitual place, using specific tools in a specific order, and other elements of the accustomed process. In the past these rituals alerted the addict’s body to what was about to happen. The steps that the addict took prepared body and brain for the physiological onslaught of the drug.

Cool-down as Ritual

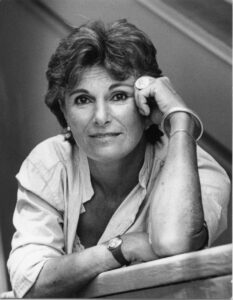

Fortunately, remote viewing is not so grim as that. But a similar principle may be involved. We seem to have more success—or at least, we seem to be more mentally prepared—for remote viewing if we have some kind of pre-remote viewing ritual. Early SRI remote viewing subject Hella Hammid had a pair of “lucky socks” that she wore any time she remote viewed. And remote viewing legend Pat Price would always take his spectacles off before a session and polish them with his handkerchief—so he could “see better,” he said.

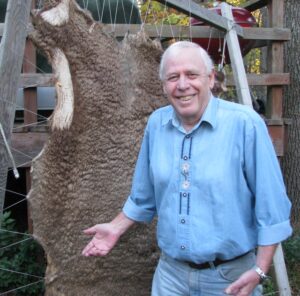

Many of the remote viewers I know have some kind of pre-session process he or she goes through. It might be extensive—ranging from my own heavy metal cool-down, to the elaborate self-administered massage introduced by Courtney Brown when he created his own version of CRV (which he named “scientific remote viewing”). The late Mel Riley was fond of doing Native American-style beadwork on a deer hide he had tanned himself.

Other approaches might be short and sweet. But any of them can serve the function of ritual. Even if your cool-down only involves you going to the place in your house where you always do your remote viewing, picking up the pen you always use, and arranging the blank paper as you always do before you start, it may serve you as a pre-remote viewing ritual. All this prepares your system for the coming effort. Similar to the more complex pre-session “rituals” others may use, even the simpler ones can lead you into the frame of mind that serves as your remote viewing starting point, readying your subconscious to open up to the coming wrestle with your analytic mind.

Cool-down and Meditation

Some remote viewers may either intentionally or unwittingly be practicing a version of meditation as their own form of cool down. Research has shown that those with a habit of meditation tend to master ESP (extrasensory perception) tasks, such as remote viewing more quickly or easily than those unaccustomed to meditative practices.

Researchers haven’t reached firm conclusions as to why meditation is helpful, but there are some tantalizing hints. Accomplished meditators report that they can significantly quiet the internal dialogue each of us experiences nearly constantly. Meditation also tends to focus inner attention, enhances relaxation, and decreases attention on distracting external sensory input.

These meditative results would naturally contribute to helping resolve both of the two biggest challenges to remote viewing success: Learning to recognize the subtle impressions that carry the experiential and informational data into the viewer’s awareness; and either avoiding or transcending mental noise (especially analytical overlay, or AOL) that often works to obscure that data. Anything that can help either of these processes is likely to be an enhancement.

To be sure, meditation in the classic sense is not necessary for remote viewing success. Plenty of individuals who have never formally meditated a day in their lives have been highly successful at remote viewing tasks. All the data shows is that meditators tend to do better out of the starting gate in ESP tasks. It’s possible that other forms of cool down may accomplish similar things as meditation, in terms of calming the inner dialogue, enhancing relaxation or damping down sensory “noise” from a viewer’s surroundings. We don’t care what it’s called, so long as its helpful.

Cool-down as Nuisance?

Now that I have covered the benefits and uses of cool-down, I have a confession to make. Over the years I have begun to wonder if having to do an extensive “cool down” may create an unnecessary problem. I confess that there were numerous times when I should have done a remote viewing session, but didn’t feel like the conditions or time available were sufficient for success. Usually that was because there wasn’t a way to do my “cool-down” properly. I would think: There’s no comfortable place to lie down. I don’t have my music with me. There’s no privacy–people could walk in while I’m trying to relax and disturb me.

I was telling myself it would just be “too hard” to get to the place of confidence that I needed to for success. Gradually I came to suspect that maybe this was simply an excuse not to remote view.

The remote viewing demonstration sessions I do for each of the controlled remote viewing classes I have taught since shortly after I began instructing civilians in 1997 gave me some insight. In a demonstration setting, I had to do the best I could without a “cool-down.” I needed to come through for my students, but there was literally no opportunity for any more than a minute or two cool down, even though in the regular operational remote viewing sessions I continued to do outside of class I still went through my full routine.

But during classes I had to cut it short. This generated anxiety. If I wasn’t fully “prepared” the way I was accustomed to, might I not fail embarrassingly in front of my students? I got through the anxiety by assuring them that, while the lack of my usual preparatory routine might lead to failure, I would do the best I could–just don’t expect me to succeed every time.

And in any case the goal of my demonstrations was and continues to be not to prove to them that remote viewing worked (they would be proving that to themselves in their own sessions). My purpose was to show them how the process flowed for someone with years of experience and demonstrate the objectification process, and how the perception and recording of responses and impressions should be paced. Failing to get the target didn’t matter if that goal was achieved.

I still went through a short cool-down ritual, arranging paper and pen, closing my eyes for a few calming breaths, writing down my personal inclemencies, then the start time. Then launch.

Do you really need cool-down?

Gradually, I began to notice something interesting. I didn’t seem to “fail” in my demonstration sessions any more often than I usually did with my standard cool-down. As I have many times explained, remote viewing is never 100% successful. Even the best, most experienced viewers fail to adequately describe the target a certain percentage of the time. Perhaps cool-down wasn’t as important as I had been telling myself? Maybe I didn’t need to take that extra time just to get into what I had thought was “the right mood”? And I began to let go of the feeling that I “needed” an extensive cool-down to succeed.

This tied in with something Palyne Gaenir, an early remote viewing civilian enthusiast—and one of my students—had observed. People often ask whether remote viewing requires a viewer start off in an altered mental state. Palyne observed that in controlled remote viewing one need not begin in any particular altered state. Instead, the carefully-designed process works to induce its own mild altered state as the viewer goes deeper into a session. You start out stone-cold sober, so to speak. But by the time you reach the end of a lengthy session you become (as Skip Atwater joked back in the original Fort Meade remote viewing program) a little “dingy.” After one of us completed an intense session, Skip would give the order to “Go hug a tree!”—in other words, go outside for a walk or do some other kind of physical activity to regain one’s mental equilibrium.

In one instance viewer Mel Riley walked out of the operations building after a particularly intense session and without realizing it unconsciously tossed his car keys into the trash dumpster parked next to our headquarters building. “Why did you do that?” his companion asked. “Do what?” Mel responded. As near as Mel could figure, it must have been his subconscious telling him he was in no shape to drive.

So this is the counsel I give my students today: A little ritual is fine—maybe even involving some meditation. But relying too much on an elaborate “cool-down” procedure may become a crutch you use to avoid diving into the remote viewing pool.

Unless, of course, you have a reason similar to the one I secretly had when working as a military remote viewer. For me as a sleep-deprived single parent of three elementary school-aged kids, cool-down was a great excuse to legally take a catnap on Army time with my commanding officer’s blessing. “Oh, I’m not taking a nap. I’m cooling down for my remote viewing session!” It worked like a charm.