On my first day in Army airborne training I learned how not to take a break. Two hours into the routine of drills and running, our platoon’s Black Hat (as sergeants who run the training are called) halted us and said he was going to teach us how to “take a break.” He ordered us to “fall out,” which is supposed to mean that soldiers can relax and move around at will. So, naturally, we began sauntering over to the shade of a nearby tree.

“Where do you think you’re going?” bellowed the Black Hat. “Did I tell you to go anywhere? Get down and knock ‘em out!” We all instantly dropped to the ground and started doing pushups. “Get up!” We jumped to our feet. Regulations said they couldn’t make us do more than 20 pushups at a time without a rest. How long a rest wasn’t specified. The moment we were back on our feet the sergeant yelled again “Get down and knock ‘em out!” This went on for 15 minutes or more, punctuated only with “You’re going to do this until I’m tired!” from the Black Hat.

By the time it was over, we had each done around 250 pushups and I had a shoulder injury that kept me from saluting anyone for the next week–a fate worse than death for a newly-minted 2nd lieutenant. I’ve never looked at taking a break the same way since. And, just as I learned how “not to take a break,” too many beginning remote viewing students have learned how not to take a break as well. They just haven’t realized it yet.

This blog exists not just to explore interesting thoughts and ideas about remote viewing and non-local consciousness, but to offer occasional tips and tools that will help you in your engagement with remote viewing and remote perception. This post is one of the latter. In this installment, I’m not going to talk about how a jump school trainee “takes a break,” but how a remote viewer is supposed to do it. Fortunately, there is no pain to this version of that lesson.

If you are interested in remote viewing, then whether the words you’ve heard are “stray cat,” or the traditional “analytical overlay,” or another term altogether, there is something you need to know. That “something” may at first seem trivial, but I guarantee it makes a difference.

First, a brief tutorial for those who don’t yet know all the remote viewing ropes. The original term was (and still is) “Analytical Overlay” (abbreviated as “AOL”–an acronym created by remote viewing’s originator Ingo Swann well before America Online was even a thought in Steve Case’s mind!). A remote viewer encounters analytical overlay when his or her conscious mind (which for the most part hangs out in the left brain hemisphere) imperfectly analyzes real ESP impressions in the viewer’s mind and misrepresents them as something quite different from what the actual target is. An example I often use is when the correct target is the Eiffel Tower, but the viewer’s left brain instead misinterprets it as a steel girder bridge.

It happens, too, that the left brain sometimes simply “guesses” – that is, makes things up altogether–and offers these guesses as possible explanations for the target. So if the target were the Eiffel Tower, the conscious mind might for example offer up “Mount Rushmore” instead, even though the two have almost nothing in common.

One term I mentioned earlier, “STRAY CAT” (abbreviated “SC”), was coined by former military remote viewer Lyn Buchanan and offered as an alternative for the preferred “analytical overlay” term. It stands for “Subconscious Transference of Recollections, Anxieties, and Yearnings to Consciously Accessible Thought.” Both AOL and SC are names for the same mental phenomenon, so from here on I will use the original term AOL or “analytical overlay.”

In my remote viewing training courses, I teach my students how to first distinguish AOL from real signal-line information, then how to manage it properly as they encounter it in their sessions. When novice viewers identify an AOL as they are doing their remote viewing work, I teach them to say out loud, then write “AOL break” (or they can abbreviate it “AOL bk”) with a brief description of what the AOL is in the right margin of the page they are on. This matches what the originator of remote viewing, Ingo Swann, required of us when he was training my colleagues and me years ago.

Unfortunately, I see almost no one other than my own students doing it that way. Most remote viewers who have been taught the skill since remote viewing became public have learned only to say and write “AOL” (or “SC”)—leaving out the “break”—along with a description of what the false impression was. Then viewers often go into great detail describing these impressions. They do this with the best of intentions, because they have not been taught Ingo’s theory and instruction on this matter.

Ingo Swann and his partner in the RV developmental process, Hal Puthoff, conceived of remote viewing in general, and controlled remote viewing (CRV) in particular, as being driven largely by the subconscious mind (or “unconscious” mind, as some label it). That means, necessarily, that communications between the consciously-aware and subconscious parts of our minds are important for successful remote viewing.

For proper remote viewing, you need your subconscious mind to receive the remote viewing signal as cleanly and clearly as possible, and pass the signal along to the consciously-aware part of your mind, where it is decoded and expressed in a form that others can understand. But the subconscious mind can become confused if conscious analysis generates a false story. If your subconscious does become confused, it may filter the incoming RV-related data, distorting it to match that false story, and you the viewer become hopelessly stuck in an AOL.

Ingo’s guidance to avoid this situation consists of two parts. First, declare a firm, definitive “break” from the false story. Merely saying and writing “AOL” is insufficient, as it doesn’t instruct the subconscious to actually break away from the false story. The viewer is counseled also to say explicitly and write “break” (or “bk”), a decisive instruction to his or her subconscious to disregard the story line being developed as an AOL by the left brain. Otherwise all you’re doing is identifying something as an AOL, but not telling your consciousness to “don’t pursue that” and to go back to the signal line.

But that is only the first part of it. Viewers are also to avoid elaborately describing the AOL in detail. It is, of course, necessary to identify the AOL to a small degree so the subconscious knows what it is supposed to “break” from. But to dwell on the AOL, to describe in detail what you, the viewer, seem to be perceiving risks becoming too enamored of the AOL—“falling in love” with it, if you will—making it harder for the subconscious to avoid becoming entangled in and break away from the false impressions.

As I said at the start, this may seem like a small thing. And, in fact, remote viewers have produced successful sessions even when oblivious to the Swann/Puthoff principle about “taking breaks.” But one wonders how much more success remote viewers might see if they actually do it the way Ingo instructed. Since it is a “small thing,” it makes sense to give it a try and see if it enhances your viewing. It certainly won’t hurt.

—–

Afternote:

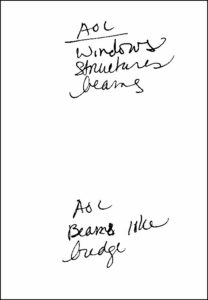

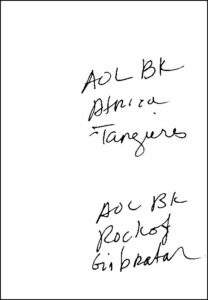

When my students complete the week-long in-residence part of my courses, their homework is to do ten remote viewing sessions which I score and correct individually, then return to them. These ten sessions reinforce the skills students develop in the classroom, and get them on their way to remote viewing mastery. I get plenty of opportunity to see where and how new viewers can go astray, and I have lots of experience helping them along. Recently I received one of these homework sessions from a student. As you can see, she forgot to follow the “break” rule in some of her early homework sessions, but soon got into the habit of declaring an AOL break appropriately.