I received an interesting phone call one day last fall (September 28, 2015 to be exact). It was from my medically-retired Marine friend, whom I will call simply “Dru,” as he is protective of his privacy—to the extent of pulling down his Facebook page a few years back, and only accepting calls from phone numbers he recognizes (in my case, that means only from my cell). Dru had called to share something he didn’t quite know what to make of, but thought I might offer some insight. He discovered he was having bits of spontaneous intuition, mostly about personal and family matters that he couldn’t possibly have been able to know by normal means. These intuitive bursts were occurring more and more often, and from the tone of his voice I was impressed that he found them disturbing and fascinating in equal measure. I was prepared to believe his story, but I as I always am, was also inclined to caution in what I was willing to believe.

I regularly get calls and emails like this from both friends and strangers. Since I’m only hearing their stories over the phone or via emails, I often can’t be sure whether what they’re telling me is real. I know that imagination can play a role in what people think may be happening to them. There are times when what they are experiencing is truly real. Yet other times they may believe they are experiencing non-local intuition, even if they actually are not. So I am never skeptical– just always careful.

Dru and I talked for awhile. I don’t remember many specifics of what he said about his new-found talent. I know I reassured him that these things are normal, and even congratulated him on his developing ability. I neither believed him nor disbelieved him, since there was no confirming evidence, but I gave him fully the benefit of the doubt. Both of us had other things that needed doing, so we soon ended our conversation with promises to speak again soon. For me, one of those things involved a quick trip to the Parowan Gap.

* * *

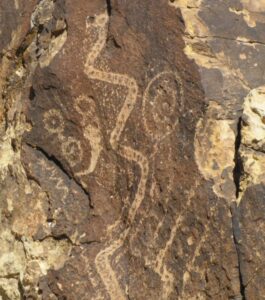

Step out my front door, drive for barely twenty minutes, and you will arrive at one of the densest concentrations of ancient Native American rock art in the Southwest. Centuries ago, the Fremont People, since followed by many others, chiseled through the dark surfaces of massive boulders and into the lighter layers beneath, revealing mysterious symbols, figures, and scenes from prehistory.

Called the Parowan Gap, the site is a giant cleft in the earth that from ancient to modern times has allowed tight passage between towering cliffs. At the summer and winter solstices the setting sun stabs through the Gap, illuminating rock cairns placed hundreds of yards beyond by the ancients. Some of the rock art (literally “petroglyphs,” or “rock symbols”) serves an astronomical purpose. A huge carving on an eastern-facing slab displays a diagram of the gap itself, annotated with various symbols marking astral and seasonal events throughout the great yearly cycle.

I love to bring my remote viewing students to this mystical place. In the sagebrush-perfumed breeze fresh off the high desert, ages of wisdom soak through your skin and into your bones.

But it is not all about the heavens and the seasons. There are also snakes.

I don’t literally mean the actual slithery, hissing kind (at least, not yet), but rock-art depictions of them, undulating up the cliffs, painstakingly chipped into the prehistoric rock patina by craftsmen so long gone they are not even now a memory. Snakes were important to the people who once lived here. And snakes are important to the spirit of this place. They symbolize wisdom, and magic. And protection…and danger. And that is where today’s story begins.

September 29, 2015. Less than 24 hours before I was to depart for Paris to speak at the “Day of Intuition” conference, I had come to the Parowan Gap to borrow some of its materials. None of its artifacts, mind you–just some pebbles to use as an object lesson for my audience in France. There’s nothing illegal about gathering a few pebbles from the foot of the cliffs. The area is managed by the Bureau of Land Management, so collecting a handful of rocks is no problem, as long as they aren’t antiquities. Yet I couldn’t help but feel anxious about what I was planning to do. It was almost as if the place itself had certain reservations about my pilferage. It might allow me to “borrow,” but once I was through, I had darned well better bring back anything I took.

As I was wrapping up my collecting, another visitor ambled by, and we struck up a conversation as we went back to our cars. It turned out he was from southern California, and on his trips north regularly stops by the Gap to renew his admiration for the aeons-old patterns etched into the stony walls. Conversing, we walked side-by-side along the recently-laid cement path, crowded a little by seasonal desert brush that typically grows up quickly during the hot months, creating a bushy border that encroached on our way.

Abruptly – so suddenly that I even surprised myself– I leaped sideways propelled by only one foot, with my left arm shoving my new acquaintance forcefully off the far edge of the sidewalk. His face showed a look of shock and astonishment at the aggressive move, just as I uttered three words that instantly explained my action. “Rattlesnake,” I gasped. “A big one.”

And indeed it was. In the split second before my sideways leap I saw my right foot in mid-step describing an arc that would have brought it down squarely on the plump tail of an enormous western diamond back rattlesnake. His tail and rattles stuck out easily twelve inches from under a green Russian thistle along the edge of the sidewalk, motionless. I came within six vertical inches and a half second of stomping on it, which almost certainly would have earned me a nasty, venomous bite in return.

The snake was just as surprised as we were, and immediately sucked his tail under the bush to join the rest of his body. So startled was he, that we are able to come to a stop on the far side of the walkway, about eight feet away, and peer under the edge of the bush before he even started a warning rattle. He was now very clearly upset. In moments, he wound his rattles up to an angry blur, and coiled his fore-body, poising his massive head to strike should we get any closer.

My new friend snapped some photos with the camera he carried, though any photos would show mostly bush and very little snake. Then we and the annoyed reptile went our separate ways. I took my encounter as a warning to treat well what I had borrowed–the symbolic nature of the confrontation reinforced by the fact that I had never encountered a snake there before, and never since. The next day I was off to Paris, where I had both pebbles and an unexpected story to share with my French audience.

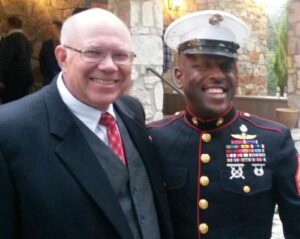

Dru and the snake came together a month later, on November 3rd. My new book was finally published, and I had a book signing scheduled for November 14th in Austin, TX. But there was a possible conflict. I was going to Austin to attend Dru’s wedding, and the book signing was an after-thought. So to make sure my newly-scheduled event wouldn’t interfere with any wedding-related plans Dru had, I gave him a call. As we talked, he again brought up his new intuitive experiences. He got right to the point. “Did you recently have something to do with a snake?” he asked. “A snake?” I said, playing dumb. “Yes,” he confirmed. “On a path or something. You were walking along with someone else and came across a rattlesnake and almost stepped on it.” I asked him cautiously, “Did I tell you about that story?” “No…” he answered. “So something did happen?”

I considered for a moment, then gave a condensed version of my experience with the rattlesnake. As I finished, I asked “Are you sure we haven’t talked about this since then?” I suspected I might have told him the story in a previous phone call and he had forgotten the conversation but not the story. “No,” he insisted. Still, knowing how fickle human memory can be, I dug into my cell phone’s call history after we hung up, just to check.

As I said before, Dru only accepts my calls if they’re from my cell, and that’s the only phone he calls me on. Though I remembered no such call, I could easily verify whether we had talked since the snake incident. If my phone’s call logs did indicate such a conversation, then I couldn’t rule out the possibility that I told him the story earlier, he had forgotten, and was remembering the story as if it were coming from the deep recesses of his mind. I turned to my phone and carefully thumbed through the listings. I found our conversation from September 28th, the day before the snake incident. I found the call Dru and I had just completed. But there was absolutely nothing in between. We had not communicated since my encounter with the snake. Dru’s story had to be authentic.

Some might think that this is not a story about remote viewing. I am not so sure. First, though the intuitions Dru gets come spontaneously (he wasn’t, for example, trying to remote view what I was up to that day), he did describe the snake event the way one might a high-quality remote viewing experience. But further, what really is the difference between non-local intuition and remote viewing, anyway? Remote viewing usually includes some kind of methodology and certain standard protocols. Intuition is more spontaneous, more of a natural, or “wild” sort of thing.

But fundamentally, isn’t it likely that they share the same source, the same innate ability that each of us seemingly is born with, and can develop for ours and others’ benefits, if only we can find the switch to turn it on? For some, remote viewing provides that switch. Others seem to find it on their own, almost accidentally. Like Dru…and maybe that snake.