Remote viewing traces its roots at least as far back as the Greek historian Herodotus. Herodotus recorded the story of Croesus, the king of Lydia who, in the 6th Century BC successfully tested the psychic abilities of the Oracle of Delphi. Modern remote viewing history dates from a number of pioneering experiments performed in the late 1960s and early 1970s at the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR). The focus of these experiments was New York artist and psychical researcher Ingo Swann.

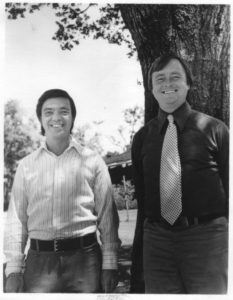

The ASPR experiments ultimately led to Swann teaming up with Dr. Harold E. “Hal” Puthoff at Stanford Research Institute’s Radio Physics Laboratory in Menlo Park, California. Working together, Puthoff and Swann–and soon a number of others–conducted a series of ever-more sophisticated experiments, further developing the approach that Swann had originally named “remote viewing.”

The earliest Swann/Puthoff experiment quickly attracted the attention of the Central Intelligence Agency. In an era of disturbing revelations from behind the Iron Curtain, it appeared that the Soviets were heavily financing experiments in various psychic phenomena, and finding success. The CIA needed to know if there really was anything to the sorts of things the Soviets were investigating and funding with such enthusiasm. If the phenomena turned out to be real, they could pose a significant threat to national security. They might also prove useful to our own defense establishment.

Representatives from the Agency brought a select few projects to Swann and one of his colleagues, Pat Price, who also had impressive remote viewing talents. The results in some cases were spectacular, and in all cases sufficiently intriguing that the CIA kept coming back for more. This led to formal research contracts between the Agency and the now-renamed SRI-International.

However, in the mid-1970s a number of scandals involving the CIA forced it to divest itself of any controversial activities in which it was at that time engaged. Remote viewing counted as being controversial. Oversight for the program passed first to the US Air Force, and then to the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) under the program name “Grill Flame.” In the meantime, the US Army began its own program at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland in 1977, and by 1979 this effort was administratively moved under the Grill Flame umbrella while still remaining an Army-managed program.

Founded by Lt. F. Holmes “Skip” Atwater and Maj. “Scotty” watt, the Army’s remote viewing program originally began as a counter-intelligence effort, with the mission to evaluate through “reverse engineering” how vulnerable US secrets were to psychic spying. So successful was this effort, that Department of Defense and Army officials decided to change the program’s assignment. Now, instead of merely evaluating adversaries’ ability to spy on the United States using ESP, Grill Flame’s mission became to actively collect intelligence against foreign threats–thus turning the tables on America’s Cold War opponents.

Unfortunately, psychic spies were not especially popular among many generals, upper-level bureaucrats, and politicians. By the early 1980s most of the Army program’s cousins in the other military services were gone or moth-balled, and DIA had scaled back its Grill Flame effort. In 1980, the Army itself lost all funding for its remote viewing program. However, Major General Albert Stubblebine, who commanded the Army’s Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM)–parent headquarters for the Army’s part of Grill Flame–took a personal interest in the psychic program. In 1983 he directed that the program be redesignated the “INSCOM Center Lane Program,” and be funded directly from INSCOM’s budget.

By this time, Swann and Puthoff had developed an improved methodology for teaching remote viewing known as “coordinate remote viewing” (later renamed “controlled” remote viewing), or “CRV.” Along with Center Lane’s debut, the Army signed contracts with SRI-International to train military and DoD civilian personnel in the new remote viewing technique, with Dr. Hal Puthoff and Ingo Swann managing the training at SRI facilities in California and New York.

Ultimately, the Swann/Putoff team trained four members of the Army’s Center Lane program. These were Capt. Tom McNear, Capt. Bill Ray, Army civilian Charlene Shufelt, and Capt. Paul H. Smith. A member of another Army intelligence unit, Capt. Ed Dames, was included as a temporary addition to the training. With their training completed, these individuals would go on to form the core of military remote viewing, and to train various new remote viewers later selected for the program. Eventually some of them would bring remote viewing to the outside world.

In early 1986, the Army transferred the INSCOM unit to DIA. DIA changed the program’s unclassified name to “Sun Streak,” though the physical location remained at Ft. Meade. In late 1990 the program went through yet another name change–this time to “Star Gate,” by which it became known to the world upon its declassification in 1995.

During its lifetime, the remote viewing unit collected intelligence against a broad range of targets: strategic missile forces, political leaders, narcotics operations, research and development facilities, hostage situations, military weapons systems, secret installations, technology developments, and terrorist groups. The list was staggering, and the successes were many–in some cases, even spectacular.

But Congress directed that the CIA take back responsibility for the program from DIA in 1995–and the CIA didn’t want it. Under the guise of an “objective” study by the American Institutes for Research (AIR), the CIA commissioned the services of one of the most prominent skeptics in the country. The end result was a study that falsely claimed to show that the RV program was useless as an intelligence resource. On June 30, 1995, the CIA terminated Project Star Gate and promised to declassify its holdings.

CIA officials no doubt thought they had seen the end of remote viewing. But their action had unintended consequences. When the Agency revealed publicly that remote viewing existed, and then declared that it “didn’t work,” it made it impossible for the government to keep it out of the hands of civilians. Several of the former military remote viewers decided to take their versions of the story to the world.

Canceling the Star Gate program turned out to be a great blessing, as it freed remote viewing from the shackles of secrecy and made it available for dissemination to any and all who wanted to learn about it. That act made it possible for RVIS, Inc. to exist and to promote our ongoing mission of spreading the knowledge and skill of remote viewing. And that part of remote viewing history has just begun.